Hypersensitivity And The Return To Work: Post-COVID Anxiety, Uncertainty And Irritability

As the COVID-19 pandemic comes to an end, Americans are contemplating how best to return to some semblance of normal in their personal and professional lives, and how they’ll be able to shed the anxieties of the pandemic to handle the stress of resuming work in an office.

A year of living in hibernation has made many people more sensitive; a sharp comment, a side look or even the absence of a smile can leave people anxious and angry. Now, imagine what that will look like in a busy workplace where large numbers of people exist in close proximity for hours on end. It’s likely to look something like this:

One person we spoke to complained to executives and coworkers about the feedback received from a supervisor related to a high-visibility project. The feedback was constructive in nature, but the employee was close to filing an actual human resources complaint based on the fact that she didn’t feel appreciated and felt offended by the feedback received.

No one is quite surprised individuals are hypersensitive to even the most well-intentioned feedback or mildly caustic observations compared to how they responded a year ago. Fear and anxiety about the virus and its attendant suffering triggered strong emotions, and those emotions are likely to resurface among colleagues in the workplace.

But what is hypersensitivity? Emotional sensitivity refers to the ease or difficulty with which people respond to various situations. This trait varies on two dimensions: one assesses how tuned in people are to their own feelings, and, the second, how sensitive people are to others’ feelings and emotions.

Symptoms of emotional hypersensitivity include being highly delicate to physical (sounds, smells or touching) and/or provocative stimuli. Research shows that stress, along with major life changes such as a death in the family, financial worries, persistent insomnia and a lack of exercise are the main factors that cause emotional hypersensitivity.

A senior HR manager we spoke to received a complaint from an employee who was offended because a supervisor said, “I cannot talk to you right now.” The supervisor was overwhelmed and very busy at that time. The complaint was dismissed, but the sole fact that someone filed a complaint in the first place is worrisome.

A study on hypersensitivity in the Covid context

We decided to look into the matter of hypersensitivity.

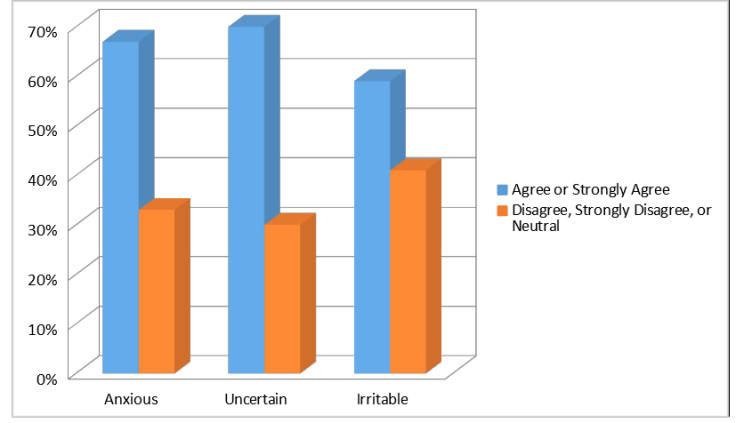

During spring 2021, we surveyed 212 working professionals and business students. The age range was 27-65, with an average age of 35. There was 42% woman and 58% men. Participants were located across 16 states and four countries. We provided participants the formal definition of anxiety, uncertainty and irritability, then asked them to respond to three questions on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

1. Coworkers are more anxious since Covid than before Covid.

2. Coworkers are more uncertain since Covid than before Covid.

3. Coworkers are more irritable since Covid than before Covid.

The results were not far from what was expected: 67 percent reported “agree” or “strongly agree” that colleagues were more anxious; 70 percent reported “agree” or “strongly agree” that they were more uncertain; and 59 percent reported “agree or “strongly agree” they coworkers are more irritable.

The survey results helped explain colleagues’ behavior, but does the same apply to managers and supervisors? One survey respondent expressed disappointment for the lack of responsiveness from a support team and emailed his manager saying, “Today, I can honestly say I am a bit disappointed.” The manager’s surprising response came back: “I am offended by the fact that you said you are disappointed.”

This type of interaction exists across all levels of the organization from employee to supervisor, manager to manager and even executive to executive. Well-intentioned feedback and an offer to assist from an colleague can easily spark a negative reaction and close off dialogue in the stressed workplace.

How employees can respond to office stress

For employees, the process of responding to workplace stress falls into three categories: understanding what stress looks like, managing job stress effectively and knowing where to go for help. The goal of this process is to resolve conflicts and build resiliency. Symptoms of stress include feeling anger, nervous, anxious, sad, depressed or burned out.

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) offered some helpful tips to better manage anxiety inside work: communicate openly with coworkers, supervisors and staff about stress; recognize things that cause stress and work together to identify solutions; set expectations and share them widely; and access mental health resources that may be available through the office.

Skynova, which supports businesses with invoicing and accounting needs, surveyed 1,165 American workers and found they are already finding ways to soothe their anxieties. Before the pandemic, employees, on average, took four breaks at work during the day, with just 23% of people reporting more than five breaks. Once the pandemic began, survey respondents said they took five breaks from work, on average, with 34% of people taking more than five breaks.

To manage work anxiety personally, whether employees are working remotely or in the office, the CDC recommends developing a consistent daily routine, keep a regular schedule, take breaks from work to stretch or call colleagues, go outside for a break and do enjoyable activities during non-work hours.

Finally, CEOs, VPs, directors and managers must be aware that their teams might experience levels of anxiety and hypersensitivity as they return to work, and it behooves leaders to help employees find ways to reduce stress and decompress inside and outside the office.

For employees, the emphasis should be on understanding and analyzing personal needs and emotions, and then asking employers for multiple daily breaks and flexible work schedules. Most importantly, it is essential for workers to pay close attention to what they are feeling and why, and then act to alleviate anxieties and stress.

James R. Bailey is a professor of leadership development at the George Washington University School of Business. He is the author of five books and hundreds of articles, and the founder and editor of Lessons on Leadership.

Anca Alexandrescu is a branch manager for the Department of Homeland Security and a George Washington University MBA student.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.